When Rome Tried to Forget Its Own Emperor

There’s something deeply human about wanting to erase what embarrasses us.

But the Romans, as usual, took this to another level.

When Emperor Nero died in 68 AD, Rome didn’t just move on — it tried to wipe him from memory. Statues were smashed, inscriptions chiseled out, portraits destroyed. In an age before photographs or the internet, the only way to “delete” someone was literally to carve them away from stone.

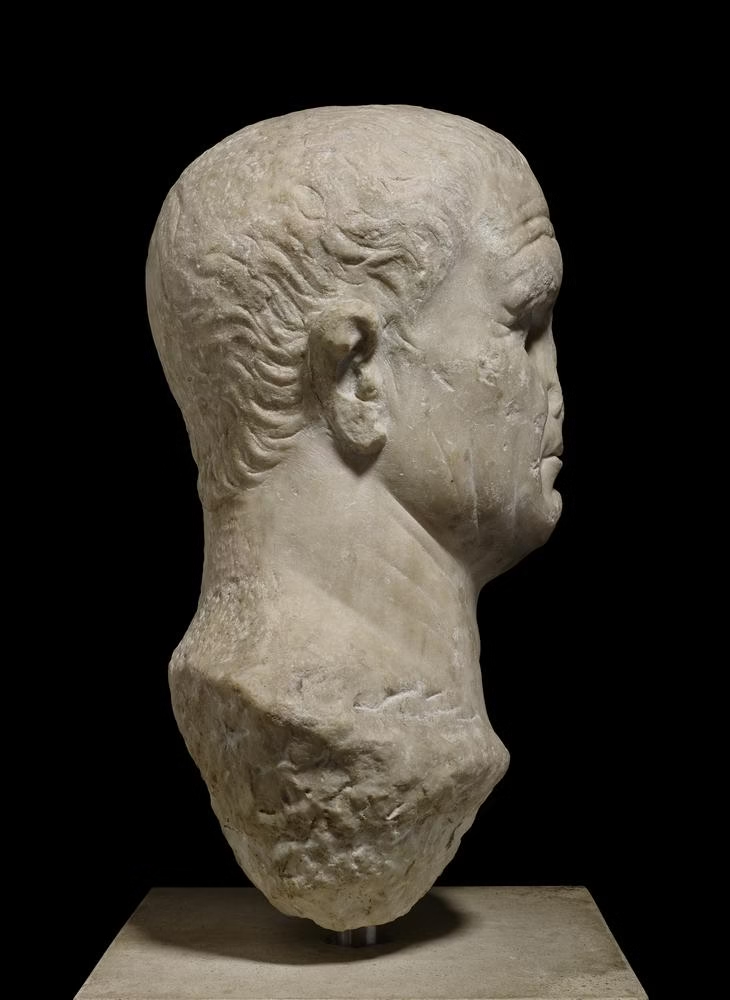

Image: Marble bust of Nero with erased features. British Museum (Public Domain)

Yet here’s the twist: the Romans never actually called this “Damnatio memoriae.”

That phrase — which today fills history books, museum labels, and documentaries — was invented more than 1,500 years later.

The origins of the term “Damnatio memoriae”

The term Damnatio memoriae, Latin for “condemnation of memory,” first appeared in the 17th century, coined by scholars trying to describe the practice of erasing someone’s name or image after disgrace.

The Romans themselves used other expressions — like

- abolitio nominis (erasure of the name),

- abolitio memoriae, or simply

- decrees that “the name be removed from all inscriptions.”

These were bureaucratic acts, not mystical rituals. The Senate didn’t curse Nero’s soul; it ordered his official memory erased from public view.

For example, a dedication might originally read:

“NERO CLAVDIVS CAESAR AVGVSTVS GERMANICVS…”

But after his downfall, masons were sent to chisel out every letter of his name, leaving ghostly scars still visible on Roman monuments today.

Stone, Power, and the Fear of Being Forgotten

In ancient Rome, to be remembered was everything. Names carved in marble meant immortality — the promise that one’s deeds (good or bad) would outlive the body.

So when a ruler’s name was erased, it was more than vandalism; it was a symbolic execution of their memory. The Romans believed that without a name, the person no longer existed in the collective mind of the city.

Yet even in erasure, the irony is that Nero survived.

Every missing name on a monument whispers his presence. Every scar on a travertine block testifies to him. Rome never truly forgot Nero — it immortalized his absence.

Travertine, Time, and the Marks That Remain

This story isn’t just about emperors. It’s about stone as memory.

Roman builders used travertine, the creamy limestone from Tivoli’s quarries, for everything from the Colosseum to humble altars. It was durable but soft enough to carve — and to erase.

When Nero’s inscriptions were destroyed, it was often on travertine. The same stone that carried his glory became the canvas of his disappearance.

Even today, walking through the Forum or along the Via Sacra, you can find pitted letters and empty frames where names once stood. Those silent voids are Rome’s own memory wounds — the material trace of censorship.

(👉 You can read more about how travertine became the stone of Rome in this post)

Why Erasing Nero Made Him Eternal

There’s a paradox at the heart of all damnatio memoriae:

the harder you try to erase someone, the more visible their absence becomes.

Every chisel mark meant to destroy Nero’s image now draws attention to his story. His missing name, the hollow niches where his statues once stood — they tell us more than any surviving inscription ever could.

In a sense, Nero achieved what all emperors desired: immortality. Not through admiration, but through the impossibility of forgetting him.

A Lesson Etched in Stone

History has a strange sense of humor.

The Romans tried to erase Nero. Centuries later, we coined a beautiful Latin phrase to describe it. And now we discuss that phrase endlessly, giving Nero more fame than ever.

In the end, the stones of Rome don’t just preserve the past — they record our attempts to rewrite it.

Maybe that’s why the city still fascinates us: it remembers everything, even the things we tried to forget.